1944 Failed his conscription exam due to pleurisy. 1945 The end of the Second World War. 1948 Moved to Tokyo. 1950 Started working as a literary critic and art critic. Became politically active by participating in strikes. Supported underdeveloped countries. 1954 Joined the Japanese Communist Party. 1962 Expelled from the Communist Party. 1999 Was diagnosed with cancer and hospitalized for two months. 2003 Lives and works in Tokyo. |

|||

Hariu Ichiro became known as an outstanding activist, he earned admiration as an art and literary critic who emphasized the importance of revolutionizing public consciousness. |

|||

Sato: When I was still living in

Japan, I wasn't able to do any creative work. I tried but there were too

many things that occupied my mind and I always felt short of time. I didn't

realize then that my life was so heavily influenced by the media. It was

only after I left Japan that I became aware of the problem. I was engaged

in a lifestyle dictated by conglomerates and media standards. We Japanese

do not have a historical awareness of individuality. Therefore we became

very self-centered when our material desires became acknowledged. Sato: When I was still living in

Japan, I wasn't able to do any creative work. I tried but there were too

many things that occupied my mind and I always felt short of time. I didn't

realize then that my life was so heavily influenced by the media. It was

only after I left Japan that I became aware of the problem. I was engaged

in a lifestyle dictated by conglomerates and media standards. We Japanese

do not have a historical awareness of individuality. Therefore we became

very self-centered when our material desires became acknowledged.In Japan many soldiers experienced the war as perpetrators, but most have died without having had the opportunity to talk about their war experiences. Maybe it is too late, but they did leave material like letters and diaries behind that could paint a more complete picture of what their experiences were like. I would recommend exhuming and analyzing the bits and pieces they left behind. There is a group in Japan called the 'Alliance of Repatriated Japanese Soldiers who served in China' (Chugoku, kikannsha, rennrakukai). They represent the soldiers that committed atrocities against Chinese civilians during the war. Right after the war they were caught and locked up in Chinese prisons. When they were asked why they killed innocent people, they stated they followed the orders of their officers, i.e. the emperor. Of course this was formally correct, but Russian soldiers for example, raped many women in Manchuria, without ever killing their victims. Through talking with ex-Japanese soldiers, Noda noticed that the soldiers perceived Chinese people as mere objects; they were able to remember what it was like to thrust a bayonet into the bodies of their victims, but they couldn't remember their faces. Furthermore if they would have accepted their war crimes and became self-critical, they became allegeable for release. They were well treated by the prison officers whose families could have been battered by the Japanese Army. Orchestrated by the Chinese government the Japanese prisoners were deliberately confronted with their war crimes. After their release they returned to Japan. Some of them stayed from 1945 till 1956 after having spent six prior years in Russian prisons. The Japanese government suspected that they were brainwashed to become communists in China. As a result the police made it difficult for them to find a job. They would for example, phone their employers to inform them about their past. For the returned soldiers it was very difficult to survive. They found some work in factories or became self-employed. Some of them were highly educated. To share their experiences in China they joined the Alliance and traveled throughout Japan to talk about their experiences during the war and afterwards. Now years later, as some have established themselves economically and socially, they were able to come out in public, join lectures etc. I have met some of them. When Noda Masaaki spoke to the ex-soldiers of the Alliance he came to the same conclusion as we mentioned earlier; their feeling of guilt was not very present and if they were aware of it, it was in a very abstract sense. One day some of them decided to visit the place where they had killed people. The neighborhood told them who the family members of the victims were; they came in contact with a woman who was alone because her husband lost his life in the war. This was the first time that a sense of guilt was embodied and became realistic to them.Noda described how there was no possibility in Japan after the Second World War to deal with these feelings. People became self centered; 'If we are fine, we don't have to worry about the others.' At that time, there was a lot of corruption in companies and among politicians... Short-tempered kids committed murders and prostitution among young girls became widespread. This part of the book is very convincing. During this trip my uncle told me that my father's parents knew about his struggle. They argued that gambling was always better than suicide, and hoped it would stop some day. His reaction was too extreme if you compare that with what happened to the Chinese people. Why do you think it is that we don't feel the same way for them as we do for our own people? |

|||

| Even though they have sworn to dedicate their life to Japan and the emperor, it was understandable that they operated on a very basic instinct to survive. Up until that point Oni can be used as a legitimate excuse. I spoke twice with Mr. Noda about this. He wasn't too convinced about my ideas because Japanese soldiers were indoctrinated to choose death over surrender so they never thought they had an alternative. But of course, if you are told to kill the enemy it suffices to rely on instinct. |

traditional Japanese Oni masks   videogame Oni from: Ganbare Goemon 2  |

||

As a nation we were not able to establish a system or methodology to control our instincts during and after the Second World War. We groped for it in many ways, but we didn't succeed at all. If you want to feel and understand everything through your sensitivity without the interference of logos, hard training is necessary. In Japanese culture there are a few good examples like the widespread influence of Zen, Nou (traditional Japanese dance theatre) and the Trip of Basho the poet. | From:

'First Kill' Coco Schrijber Netherlands 2001 73 min. 35 mm — That first moment, your first kill, it’s ... strange, because it’s something you have never done before. But after that, well, with me, it started getting good, the killing started getting good. — How many people did you kill? 36. And how did you keep count? Cutting their ears off. — So what would happen if you would encounter an enemy? Well, it would be either him or me. If you encountered him first you shot him and vice versa, a lot of them would hesitate, I don’t know why they hesitated, I don’t know because of total surprise, I had one get to drop on me, but I shot him and killed him. — But can you imagine that I could be able to do it, I could become a killer? Sure.How? By doing it.If I would be in that situation ...Yeah.It is not so hard? All you have to do is pull the trigger, gun does the rest. — I still dream about Vietnam, I still wanna go there, but I don’t wanna return the way they are going overthere now, I wanna go back over to kill.Why? I miss it. I have never found nothing like that. Yet they put us out there to do that and then they bring you home and expect you to behave like normal people. — Every kill you made, seemed like it made you feel a little better. In other words, there was a place that it sort of cheered you up to a certain extend, I mean you didn’t jump up and down or, you know with joy and all this, but there was a place in your heart that it just made you feel good.Could you compare it to anything? Sex. And then, that sounds bad because you know, can I say this on camera? Sex is such an enjoyable thing, you take it and compare it to killing somebody and having the same feeling and that’s where it gets at. | ||

| (Basho created the Haiku poem, in the 17th Century: In 1689 the

Basho set out on a poetry-making journey from his home in Fukugawa, Edo

(Tokyo). For about six months he traveled north through the interior and

the eastern coast, visiting well-known places, until arriving at Ogaki,

Gifu, having covered 2400 km. The

Narrow Road to the Deep North, his now famous haiku journal, was a

result of this trip. It was Basho's pilgrimage to famous places sung in

ancient poems to experience first hand the poetic sentiment of the ancients

and at the same time to seek inspiration for the creation of his haiku).

Basho tried to reach cosmic truth intuitively by using his sensitivity. It was a great achievement in Japanese culture. After the Meiji period this type of training almost disappeared completely.  Hariu: It was an important and interesting

element in Japanese culture, but what do sensitivity and mental equilibrium

mean nowadays? When you go to the store, you can obtain any kind of product

you want, all made with mass production techniques. Hariu: It was an important and interesting

element in Japanese culture, but what do sensitivity and mental equilibrium

mean nowadays? When you go to the store, you can obtain any kind of product

you want, all made with mass production techniques. Hariu: In Japan our sensitivity

is weak and our creativity lazy. If someone wants to create art with a

limited amount of sensitivity, it is a very lazy idea. In Japan the level

of sensibility remains modest, we lost a sense of purpose and the way

politics have been conducted after the war was hopeless. Sometimes you

can find very good, sensuous artwork in Japan, especially when a young

person makes a first time effort without thinking what its implication

would be. In that sense we Japanese are very good craftsmen, but if you

want to develop your way of thinking and develop the concepts behind your

expression, you need to abandon what is not important and concentrate

on what is important. The problem is that the Japanese cannot abandon

methods or ideas, because they have no sense of logic. For example, I

was told many times by foreigners that there were many different concepts

in painting. It seemed if a concept does not work, there are others, there

are many ways not one so to say. But this is not the way it is seen in

Japan. Hariu: In Japan our sensitivity

is weak and our creativity lazy. If someone wants to create art with a

limited amount of sensitivity, it is a very lazy idea. In Japan the level

of sensibility remains modest, we lost a sense of purpose and the way

politics have been conducted after the war was hopeless. Sometimes you

can find very good, sensuous artwork in Japan, especially when a young

person makes a first time effort without thinking what its implication

would be. In that sense we Japanese are very good craftsmen, but if you

want to develop your way of thinking and develop the concepts behind your

expression, you need to abandon what is not important and concentrate

on what is important. The problem is that the Japanese cannot abandon

methods or ideas, because they have no sense of logic. For example, I

was told many times by foreigners that there were many different concepts

in painting. It seemed if a concept does not work, there are others, there

are many ways not one so to say. But this is not the way it is seen in

Japan. Sato: Is that the reason why you

prefer to review literature to art? Sato: Is that the reason why you

prefer to review literature to art? Hariu: I became interested in literature

in the 1950's and 60's, because it had proven itself as a powerful tool

to capture, analyze, criticize and confront the situation and problems

in our society. I thought that would be the most effective way to contribute

to society. But tell me, where did you study art mainly? Hariu: I became interested in literature

in the 1950's and 60's, because it had proven itself as a powerful tool

to capture, analyze, criticize and confront the situation and problems

in our society. I thought that would be the most effective way to contribute

to society. But tell me, where did you study art mainly? Sato: I first studied Art at the

Goldsmiths' College in London. Before I went to the U.K. I worked as a

midwife in Japan. There art schools didn't seem to be very interesting,

because they over emphasized the technical aspects of art making. At that

time I did not intend to become an artist at all. I wanted to experience

what it would be like to live abroad. I met some really good teachers

at Goldsmiths'. It was a fantastic time to study art there. After Goldsmiths'

I went to a postgraduate Academy in The Netherlands. Sato: I first studied Art at the

Goldsmiths' College in London. Before I went to the U.K. I worked as a

midwife in Japan. There art schools didn't seem to be very interesting,

because they over emphasized the technical aspects of art making. At that

time I did not intend to become an artist at all. I wanted to experience

what it would be like to live abroad. I met some really good teachers

at Goldsmiths'. It was a fantastic time to study art there. After Goldsmiths'

I went to a postgraduate Academy in The Netherlands. Hariu: Which school did you go to

in Holland? Hariu: Which school did you go to

in Holland? Sato: The Jan van Eyck Academie

in Maastricht. In the second year of the Academy my teacher (Jon Thompson)

came to my studio and said 'Japanese artists are very good craftsmen but

they lack a conceptual approach. If you want to exhibit your work, it

should consist of a solid conceptual basis and that is the artist responsibility

in society.' It was a very strong critique about my work. In Goldsmiths'

I became familiar with conceptual thought as an incentive for my work.

I was fascinated with the character and behavior of materials. It was

an amazing world to discover but it also limited my work to a predominantly

visual experience. Sato: The Jan van Eyck Academie

in Maastricht. In the second year of the Academy my teacher (Jon Thompson)

came to my studio and said 'Japanese artists are very good craftsmen but

they lack a conceptual approach. If you want to exhibit your work, it

should consist of a solid conceptual basis and that is the artist responsibility

in society.' It was a very strong critique about my work. In Goldsmiths'

I became familiar with conceptual thought as an incentive for my work.

I was fascinated with the character and behavior of materials. It was

an amazing world to discover but it also limited my work to a predominantly

visual experience. After the talk with Jon Thompson, I stopped working for a while and thought of what I really wanted to achieve with my artwork. Later during my study I became amazed by glass. I was wondering around in the Academy, and placed a big glass tube (about 150 cm height x 40 cm wide) in the corridor. A partly blind man smashed into the tube by accident; it was a big 'Bam!' I went there and knew I had discovered something important, yet it was not clear what. It had to do with the destruction of the meaning of an object and making something else like a landscape with the same material. It included all my life's experiences; working in the hospital as a midwife, my father who disappeared when I was still a child, etc. While making work, I sometimes experienced to be entirely absorbed by it. This was both fantastic and frightening. Installation work has been very challenging to me. I have made Installations for the last 8 - 9 years. And now I wanted to do this project since I have been thinking about this project for 6 years now. I don't exactly know what writing is, but I knew I wanted to combine images and text in this project. It developed from personal matter into an interest in political and social issues; this especially had to do with my cultural Japanese background where relations between art and war have always had intimate. (After my trip to Japan this became clearer.) |

Basho Matsuo |

||

I have a question about Mugonkan (the word literally means the silenced),

the Museum that Kubojima Seiichiro has made in the small village of Nagano.

Kubojima collected the artworks that were made by art students who died

in the Second World War. I doubt whether these works were good enough

to be presented in a museum. Do you think Kubojima had other political

reasons? Hariu: Mr. Kubojima had no political

reason to open Mugonkan. You might think so, but he did not. Hariu: Mr. Kubojima had no political

reason to open Mugonkan. You might think so, but he did not. Sato: I think to experience the

war and to make an artwork about it are two very different affairs. Obviously

that does not mean to say that you when have had traumatic experiences,

you will also make a good artwork about it. Whatever the reason, Mr. Kubojima

exhibited the art students' work. I cannot imagine that the works were

artistically interesting enough to be presented in a museum. What is the

importance of making this kind of art museum? Sato: I think to experience the

war and to make an artwork about it are two very different affairs. Obviously

that does not mean to say that you when have had traumatic experiences,

you will also make a good artwork about it. Whatever the reason, Mr. Kubojima

exhibited the art students' work. I cannot imagine that the works were

artistically interesting enough to be presented in a museum. What is the

importance of making this kind of art museum? Hariu: I have been there once. Do

you know the book Kike - Wadatsumi no Koe (Listen - Voices from the deep)?

I was still a student when the Second World War ended. I had tuberculosis

and was therefore exempted from military service. Lots of my friends who

had to serve in the war died so I do understand what it is like to loose

someone dear. I become suspicious however when a Museum prioritizes certain

victims over others. This is my opinion about the Mugonkan museum. But

on the other hand, when I saw the articles left behind by the departed,

I felt deep sadness and compassion. Hariu: I have been there once. Do

you know the book Kike - Wadatsumi no Koe (Listen - Voices from the deep)?

I was still a student when the Second World War ended. I had tuberculosis

and was therefore exempted from military service. Lots of my friends who

had to serve in the war died so I do understand what it is like to loose

someone dear. I become suspicious however when a Museum prioritizes certain

victims over others. This is my opinion about the Mugonkan museum. But

on the other hand, when I saw the articles left behind by the departed,

I felt deep sadness and compassion. The reason why the presentation in Mugonkan is somewhat limited has to do with the fact that the collection is predominantly based on the artworks made by the students of the Tokyo Art University. The University kept their educational method strictly centered on concrete art. According to Ozawa Setsuko, who's a well-known modern Art historian, there were tendencies in private and public art schools that strongly leaned towards the avant-garde. Students came to study there from China, Korea, and also from lower class families in Japan. It would have been more stirring and interesting if avant-garde art works from these private schools would be part of the Mugonkan museum collection. |

Mogunkan museum, Nagano |

||

Sato: I heard that you had a relation

with the artists, Mr. and Mrs. Maruki who have made very powerful paintings

about the Atomic bomb in Hiroshima. (Fig. 1) I am impressed by their work,

have you ever worked with them? Sato: I heard that you had a relation

with the artists, Mr. and Mrs. Maruki who have made very powerful paintings

about the Atomic bomb in Hiroshima. (Fig. 1) I am impressed by their work,

have you ever worked with them? Hariu: When they were still alive,

they joined many peace movements. A private museum containing their works

was built and supported by their fellows. The director was a sister of

Mori Arimasa whom I knew. He was a French literature teacher at the University

of Tokyo. (Mori lived the last years of his life in France. He worried

so much about the future of human beings living under the threat of the

nuclear age that he committed suicide.) She wanted to stop working in

the museum and asked me to replace her. Now I am the unpaid director in

the museum. Hariu: When they were still alive,

they joined many peace movements. A private museum containing their works

was built and supported by their fellows. The director was a sister of

Mori Arimasa whom I knew. He was a French literature teacher at the University

of Tokyo. (Mori lived the last years of his life in France. He worried

so much about the future of human beings living under the threat of the

nuclear age that he committed suicide.) She wanted to stop working in

the museum and asked me to replace her. Now I am the unpaid director in

the museum. Sato: In Japan it seems there is

not so much social and political movement anymore. You work as an unpaid

director in the museum. Do you do this work out of political or social

conviction? Sato: In Japan it seems there is

not so much social and political movement anymore. You work as an unpaid

director in the museum. Do you do this work out of political or social

conviction? Hariu: Whatever I have been doing

has always been part of a social and political movement. Hariu: Whatever I have been doing

has always been part of a social and political movement. Sato: How do you define your concept

of a movement? Sato: How do you define your concept

of a movement? Hariu: I would first like to talk

about the 'Hiroshima Panels' as the 15 paintings of Mr. and Mrs. Maruki

became known. When I started to work as an art critic, their paintings

and books that represented the horrors of the Atomic bomb couldn't be

published or exhibited due to the censorship of the allied occupation

forces. Recently in one of my seminars we discussed one of the few books

about Hiroshima that were published during the occupation, it's 'The flower

in summer' by Harata Miki. Not that it was so noticeable as literature,

but the mere fact that it was published at that time makes it an important

book. Hariu: I would first like to talk

about the 'Hiroshima Panels' as the 15 paintings of Mr. and Mrs. Maruki

became known. When I started to work as an art critic, their paintings

and books that represented the horrors of the Atomic bomb couldn't be

published or exhibited due to the censorship of the allied occupation

forces. Recently in one of my seminars we discussed one of the few books

about Hiroshima that were published during the occupation, it's 'The flower

in summer' by Harata Miki. Not that it was so noticeable as literature,

but the mere fact that it was published at that time makes it an important

book. Sato: It all emerged secretly didn't

it? Sato: It all emerged secretly didn't

it? Hariu: Yes, leftist propaganda material

for example was impossible to be officially printed and distributed. Also

critical articles about the Imperial System, which the American military

occupation decided to keep intact symbolically, were only accepted briefly

after the war. Literature, artwork and propaganda that criticized the

Allied powers, was definitely forbidden. Hariu: Yes, leftist propaganda material

for example was impossible to be officially printed and distributed. Also

critical articles about the Imperial System, which the American military

occupation decided to keep intact symbolically, were only accepted briefly

after the war. Literature, artwork and propaganda that criticized the

Allied powers, was definitely forbidden. Sato: The United States never wanted

to show their disgrace. Sato: The United States never wanted

to show their disgrace. Hariu: I agree. John Dower, an American

historian, published the book 'Embracing defeat' in 2000. It deals with

the Japanese history after the Second World War. He described how Japanese

post-war society was reconstructed with the aid of America. Eventually

they would name it 'Imperial Democracy'. But the problem, he argued was

that the main incentive for the war (which had to do a lot with the imperial

system) was allowed to remain. So in the end no one was held accountable

for the war. Hariu: I agree. John Dower, an American

historian, published the book 'Embracing defeat' in 2000. It deals with

the Japanese history after the Second World War. He described how Japanese

post-war society was reconstructed with the aid of America. Eventually

they would name it 'Imperial Democracy'. But the problem, he argued was

that the main incentive for the war (which had to do a lot with the imperial

system) was allowed to remain. So in the end no one was held accountable

for the war. Sato: In Germany, responsibilities

were more clearly defined, I thought. Sato: In Germany, responsibilities

were more clearly defined, I thought. Hariu: Noda Masayuki suggested that

this wasn't really the case in Germany. Questions on responsibility and

clarity who was culpable during the war weren't different from the situation

in Japan. Many German civilians claim that the Nazis were solely responsible

for the Second World War. But the Nazi's couldn't exist without support

of the German citizens, even if they forced citizens to support them.

In Germany it has been very difficult to clarify who supported and who

was enticed by the Nazi's. Hariu: Noda Masayuki suggested that

this wasn't really the case in Germany. Questions on responsibility and

clarity who was culpable during the war weren't different from the situation

in Japan. Many German civilians claim that the Nazis were solely responsible

for the Second World War. But the Nazi's couldn't exist without support

of the German citizens, even if they forced citizens to support them.

In Germany it has been very difficult to clarify who supported and who

was enticed by the Nazi's.Recently the bestseller 'Der Vorleser' by Bernhard Schlink was published in Germany and translated into Japanese. It is the recollection of a German boy, who went to the Gymnasium and had a relationship with an older woman in the same town. He found it strange that the woman repeatedly asked him what he learnt at school. She was especially interested in the literature classes he took and asked him to read her the literature he studied. She was very pleased when he read her the books and they made love afterwards. One day, she unexpectedly disappeared from the town. A couple of years later, when he was a law student and had to go to court as an intern, he ran into her. She was pending trial, because she had worked as a guard in the concentration camps and she had maltreated the Jewish prisoners. He discovered that she couldn't read when they first met each other. She was so poor that she could not afford to go to school. After his internship, he became a lawyer, got married and kept on visiting her in prison. Every now and then he would sent her some books. She promised that she would contact him once she was released. But just before or slightly after her release, she committed suicide. That's how the story ends. Defining and clarifying the responsibility of the nation as a whole during the Nazi period only started recently in Germany; this story shows how complex the involvement and the struggle of people during and after the Nazi period was. An opposite example I experienced was during a symposium about 'Art in the future' which lasted three days and took Place in 1991 at the German institute in Osaka. There were 4 Japanese and 4 German panelists. I was the chairman during the last discussion. In the final report, the German panelists all talked about the position of art in society and culture, and about the responsibility of the artist. Curiously the Japanese panelists only talked about art in a historical and general perspective, stating which 'ism' came after that 'ism'. I was surprised by the difference. Let's go back to the 'Hiroshima Panels' of Mr. And Mrs. Maruki. Just after the bomb exploded, Maruki Iri (who was an Indian-ink painter) and Maruki Shun (an oil painter) hurried to Hiroshima to help and protect Iri's parents. They witnessed the disaster in the City's streets and started making drawings. Altogether they made a series of 15 paintings that became known as the Hiroshima Panels. In 1953 three of these paintings, explicitly depicting the aftermath of the Bomb were exhibited in Japan. At that period I was interested in artistically new, experimental, unconventional work. I felt it was important to develop a more objective view on art instead of just documenting whatever I felt when looking at an artwork. I criticized the paintings of Mr. and Mrs. Maruki in a magazine because I felt that they were too sentimental, focusing excessively on the victim's perspective. The works referred to traditional Japanese scrolls depicting images of hell which I thought, was too evocative. Later I came to realize that Mr. and Mrs. Maruki as well as their paintings have had a very big influence on the thinking- and recuperation process after the war. I had to revise my opinion... The 14th painting entitled 'Crows' in the 'Hiroshima Panels' series was made in 1972 and depicted a Korean worker who was forced to come to Hiroshima and work in a military factory. His body is shown rotting among the ruins in the streets as a crow picks it. The people from surrounding Asian countries like China, Korea and the Philippines were pleased that the Atomic bomb had ended the war. To them the bomb felt as a retribution for the horrors committed by the Japanese army. Mr. and Mrs. Maruki felt obliged to confront the Japanese public with the facts that occurred in the Asian countries. Eventually they started to paint the Japanese people as perpetrators. They made paintings about the Nanking Massacre (In 1937, Japanese soldiers looted the city of Nanking and slaughtered an estimated 300.000 Chinese soldiers and citizens and raped over 20.000 innocent women and children), the illness in Minamata (after the war Minamata had enormous pollution problems) and the battle in Okinawa. (At the end of the war the city of Okinawa became nothing more than a battlefield in Japan; one third of the population of Okinawa was killed not only by American but also by Japanese soldiers. As some of the citizens were forced by Japanese soldiers to commit suicide.) The series of paintings were the Maruki's answer to my initial criticism of their work. In their particular paintings of Hiroshima, Mr. and Mrs. Maruki tried to express a collective view of the actual situation and depicting the people as victims was the only way to achieve that. It would have been impossible to paint the scene with western standards trying to achieve a monistic and concentrated connotation. As a result, each occurrence, implying also a different moment in time, should be depicted in one image. The painting scroll therefore is a very good solution. It is natural that their paintings became like the classic Japanese painting scrolls of hell and haven. The Atomic bomb was a weapon where one could not see the enemy, but the massive explosion did cause the death of many people in one split second leaving the city completely destroyed. Imagine what it would be like to see so many dead people with keloids, burned flesh wounds, etc in the streets. In that type of situation it's no more than obvious that the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki didn't feel as perpetrators but as victims. However, it is necessary to face the fact that we were perpetrators in the war and therefore we do need to answer our critics.  fig.2 In 1953, the year I began to work as an art critic. Kawara On the artist was 19 years old at that time, when he exhibited 10 pen drawings entitled 'The bathroom series' (fig. 2). The drawings depicted the leg, hand, head and torso of a pregnant woman emerging from the tiles in a bathroom. The first time I criticized 'The Atomic bomb pictures' of Mr. and Mrs. Maruki, I thought that the view of On Kawahara's painting was the right road to take after the war in Japan. During the war Japanese people were controlled by politics and military force and after the war we wanted to get away from that. At that period it was a major argument to strive for a modern sense of ego, individuality so to say, in order to criticize and at times reject politics. Even though I had experienced the war, the extreme situation of the war continued for me in a different way; it was impossible implement a Western sense of humanism in Japanese culture. The idea of individuality was transplanted into Japanese society but it has never become a natural sensation of self. The novel 'The dark painting' by Noma Hiroshi had been published in 1946. In it he stated, 'Through egoism, i.e. self-protection and self-obsession, we should try to search for a western, scientific definition of ego'. At the time enthusiasts who valued the novel for its affirmation of a bourgeois humanism applauded this. They felt that this idea would never emerge in Japanese proletarian literature and therefore it typically portrayed the post war period. If you read this novel, you'll find the first chapter that consists of a prose poem, to be very central to the book. It describes a group of students of the University of Kyoto looking at a painting. The painting (an unspecified Brueghel remake) depicts handicapped farmers tenaciously resisting the tyranny of the Spanish dynasty in Flanders. The students discuss how it could have been possible to form a collective resistance as shown in the painting. Although the question Noma Hiroshi raises is disrupted in another part of the book (because it conflicts with his impossible dream of establishing a bourgeoisified type of individualism) the most important motive of the book was how a resistance, like the one formed by the Flanders farmers, could be possible. If you ask me, individuality should not be expressed in a personal-, but in a collective way. A sense of collective individuality should have been composed by the elements that surfaced in Japan after the total destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This was the concept of the avant-garde, supported by Takiguchi Shuzou (writer, critic and editor) Okamoto Taro (artist) and Harada kiyoteru in 1950's and 60's. This concept has been and still is my main incentive as a critic. I continue to believe in that.  Sato: Could you explain what you

mean when you use the term 'collective individuality' and how would this

work? Sato: Could you explain what you

mean when you use the term 'collective individuality' and how would this

work? Hariu: I do not know exactly. I

had close contact with the philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari.

In 2000, when we discussed the literature of Kafka, they emphasized the

boundlessness of his literary work, as the product of someone who was

part of a minority. Kafka tried to break away from his dominating father

in search of his own identity. As a Jew he tried to assimilate in an Austro-Hungarian

orientated Czech society. It proved difficult to integrate, he shifted

his focus and searched for ways to escape the environment he grew up in.

In his literature this quest is represented by references to machines

or the changing of form, from human to insect. You could conclude from

his writing that it is quite impossible to escape ones own roots. Hariu: I do not know exactly. I

had close contact with the philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari.

In 2000, when we discussed the literature of Kafka, they emphasized the

boundlessness of his literary work, as the product of someone who was

part of a minority. Kafka tried to break away from his dominating father

in search of his own identity. As a Jew he tried to assimilate in an Austro-Hungarian

orientated Czech society. It proved difficult to integrate, he shifted

his focus and searched for ways to escape the environment he grew up in.

In his literature this quest is represented by references to machines

or the changing of form, from human to insect. You could conclude from

his writing that it is quite impossible to escape ones own roots.To come back to the 'Hiroshima Panels' by Mr. and Mrs. Maruki: You can see in these paintings that people are trying to help others who are dying, but they cannot. They share a sense of indignation and despair. The dying people represent some sort of collective individuality for me. It is a good example of how a large group of individuals reach a sense of collectivity. In the Buddhist philosophy, in order to establish a sense of 'I', you need to integrate yourself with nature and the cosmos. That is to say, without disregarding oneself for the sake of others it is impossible to establish an enlightened sense of 'I'. Since the 70's, due to the then present political and economical situation, Japanese artists have become autonomous and isolated. They lost connection with society and searched for an identity by adopting mediocre ideas that differed very little from international modernist tendencies. Autonomous art assesses political, social, economical, and cultural issues of a certain era. It represents these topics in an idiosyncratic way and therefore challenges the organization, censorship and taboos of society. To strive for art's autonomy should however not imply a division from our cultural heritage by simply categorizing it as a profession subject to prevailing economical, social standards of society. According to Michel Foucault, authority is not an isolated entity anymore. In the latter definition of Capitalism, authority is latent throughout all social structures. Therefore the only possibility to discern existing control structures is by adopting the perspective of women, children, invalids, immigrants, political criminals, the elderly, the unemployed, and the homosexuals who are naturally/structurally oppressed or discriminated in society. If artists solely define themselves within existing power structures and shy away from the weak and suppressed in society they will never become truly innovative and autonomous in their expression. I would like to finish by mention a book I'm still reading, 'Empire' by Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt. It used to be a popular book in the United States before September the 11th but the U.S. government became very critical towards it after the attacks. I realize now that this gigantic empire, the United States, was established not because of territorial expansion or imperialism, but through their stronghold on the information network. Consequently, you could argue that unification through Nationalism is no longer an effective way to control people. According to Baruch Spinoza, the organization of an empire depends on how mature its general public is. So far the general public is nothing but a crowd of people, a gathering of isolated individuals. But if we succeed in organizing people in a fluid and flexible international network (e.g. how self organized political/social/artistic gatherings are conducted through the internet), we could be able to form alternative domains that balance and perhaps even overthrow national and international empires. Art appeals basically to individuals and spreads itself through flexible networks and relationships, therefore its influence could become an increasingly important part of alternative movements. |

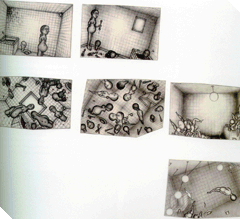

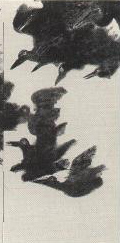

Hiroshima Panels (detail)  Crows (detail) |

||